Against Lee’s best troops

they stood their ground

By Walter Fox

Dennis O’Kane, the bearded and battle-hardened colonel of the 69th Pennsylvania Volunteers, stood on the slope of Cemetery Ridge, looking down at a weary and bedraggled band of Philadelphia soldiers. At that moment they were spread out behind a low stone wall, trying to find or make any kind of refuge from a sun that by noon had pushed the temperature near 90 degrees.

For a military disciplinarian like O’Kane, it was not a pretty sight. Some of his troops were lounging in the scant shade of a clump of small trees behind the stone wall. Others had made makeshift canopies by jamming the bayonets of two muskets into the ground, tying two corners of a blanket to the trigger guards and staking the loose corners to the ground with ramrods.

It was all that O’Kane could do to keep from striding down the slope, pulling down the canopies and reprimanding the soldiers who had constructed them. But he knew that his regiment, recruited—like himself—from the city’s Irish working class, had been without provisions for nearly 48 hours and was exhausted from marching for days from Virginia to Gettysburg under a broiling sun and torrential rains.

There was a time for discipline and a time to forget discipline, and the good officer knew when. Besides, his men had already acquitted themselves admirably the evening before, beating back a concerted attack by a Georgia brigade on the center of the Union line. The 241 unkempt troops lazing in front of him were all that remained of a regiment of nearly 1,000 men formed in September of 1861, using Philadelphia’s 10 Irish militia companies as its backbone.

In the eerie silence that followed this morning’s sporadic skirmishes and artillery duels, O’Kane had time to think. Despite their obvious fatigue, his troops were prepared for the attack that was certain to come. At his urging, they had gone out into the field beyond the stone wall and had gathered up muskets from the bodies of Confederate soldiers killed in yesterday’s fighting. Now, most of his men had several weapons they could fire before reloading.

As for morale, he knew it should be high, now that the regiment was back in Pennsylvania. At least he would point that out to his troops at the appropriate time. Still, the quiet was unnerving—and the heat, overpowering. He forced himself to recall that the day was July 3. Today, in normal times, he would be fussing with last minute details, insuring that his Irish Volunteers militia company was ready for its part in tomorrow’s parade down Chestnut Street to the State House.

Given the hostility of Philadelphia nativists toward Irish immigrants, he would make sure his company’s military performance would offer no justification for the inevitable hisses and catcalls and the occasional brickbat. And when they occurred, his men would defy the popular stereotype by ignoring them with the detachment of a Prussian honor guard.

Hannah and the girls would be proud of him.

What was a 45-year-old family man from Derry doing, standing in a Pennsylvania pasture on a sweltering summer day in a blue wool uniform?

The thought of his wife and three grown daughters jarred him out of his reverie. What was a 45-year-old family man from Derry doing, standing in a Pennsylvania pasture on a sweltering summer day in a blue wool uniform? It was not an easy question to answer.

So many things had happened so fast. The wedding in the small parish church in Learmount, the birth of two daughters in rapid succession, the long, stomach-churning sea voyage, the struggle to gain a toehold in a city where so many people despised his Irishness and religion, the birth of another daughter in America.

He would have liked a son. If he had one, more than likely he would be here in one of the 69th’s companies—if he had survived Glendale, Antietam, Fredericksburg and all the rest. What if he hadn’t? How do you deal with that?

But the girls were special, and he was fiercely protective. It was this trait that got him into trouble. He was surprised how much the hurt of the court martial still remained after nine months, but there was no avoiding what had happened.

The incident was engraved on his memory. He was then lieutenant colonel of the regiment, which was camped at Harper’s Ferry. It was a brilliant October day, and his wife and oldest daughter, Mary Ann, had come down from Philadelphia to visit. To show them the town in style, he had rented a carriage and pair.

They could not have been riding more than ten or fifteen minutes when out of nowhere appeared his commanding officer, Col. Joshua Owen, on horseback and clearly in his cups. Owen gave no sign of recognition, other than a smirk, then proceeded to ride his mount against the carriage horses.

O’Kane was aghast. Owen, a Welshman who had been dubbed “Paddy” for leading an Irish regiment, had a reputation as a drinker, but O’Kane had never seen him like this.

Owen pulled away, then turned and repeated the maneuver. As O’Kane tightened the reins on the frightened horses, he glanced at his wife and daughter who were clearly panic-stricken.

“Stop it,” O’Kane yelled. “Stop it.”

Owen pulled away again, but this time turned and faced O’Kane.

“You Irish son of a bitch,” he shouted, the smirk returning to his lips.

O’Kane could feel the blood draining from his face, but he said nothing.

Owen looked at the three of them, then turned to Mary Ann.

“Miz O’Kane,” he said, “how would you like to spend the night with me in my tent?”

Without so much as a second’s hesitation, O’Kane gave the reins to his wife and jumped down from the carriage. Passing behind the cab, he caught Owen by surprise. He reached up, grabbed Owen’s belt and pulled him from the horse.

O’Kane remembered that Owen’s head bounced when it hit the ground.

Things happen quickly in America.

It was indeed odd, he thought, that nine months later he is the colonel of the 69th and Owen is in disgrace, having been forcibly removed as brigade commander. Things happen quickly in America.

But the court martial still stung, even though he had been acquitted. Owen, who was tried the next day, was convicted on two of three charges and sentenced to dismissal, but was reinstated by virtue of his distinguished military service.

O’Kane’s ruminations were abruptly terminated by the blast of a Confederate cannon that echoed across the valley. It was followed by another, and he watched as the puffs of white smoke drifted above the line of nearly 150 field pieces that Lee had assembled in front of Seminary Ridge.

Then came a thunderous explosion as scores of cannons were fired simultaneously. With shells exploding overhead, O’Kane realized that Cushing’s Battery to the rear of his regiment on the right and Brown’s Rhode Island Battery on the left had clearly been targeted by the Rebel gunners, and, acting on reflex, he shouted to his men to get down.

It was a useless order. Trapped by the exploding shells above and the return fire that was starting to pass overhead, his troops had already flattened themselves where they had been lounging moments before.

The sky above Cemetery Ridge rained shrapnel and solid shot, and was so thick with the smoke of exploding ordinance that the sun appeared as a red ball in the haze. O’Kane, who was kneeling near the clump of trees, wondered how anyone could stand up in such a barrage, yet the two Union batteries behind him kept on firing.

A seasoned campaigner, O’Kane had seen his share of bombardments, but never anything like this. It seemed to go on interminably with no breathing space between the cannon blasts. In the midst of the mayhem, he turned to his left and saw through the smoke someone waving frantically to get his attention. It was Jim Duffy, the regimental major.

“The General’s coming,” Duffy yelled and pointed to the left of the stone wall.

Squinting to sharpen his vision, O’Kane could make out the figure of an officer on horseback riding casually in front of the Union lines, stopping occasionally to say something to his troops.

As the figure neared the left end of the stone wall, O’Kane knew Duffy was right. It was Hancock, and the old soldier was greeting his troops, oblivious to the chaos around him.

When Hancock reached the center of the wall, he looked up, smiled and waved to O’Kane, who by then was standing for a better view. O’Kane saluted smartly, recalling that the last time he saw Hancock smile like that was back in October when the General had presided at his court martial. He took the smile then to mean that Hancock had concurred in his acquittal.

The Rebel bombardment went on for what seemed like hours. Despite the terror that clearly registered on the faces of his troops, no one that he could see ran to the back. O’Kane was satisfied that the strict discipline he had demanded when the regiment was formed had now paid off.

Just then, the shelling began to slacken off, and it ceased almost as abruptly as it began. When the smoke finally lifted on both sides of the valley, O’Kane could see three lines of Rebel troops, several ranks deep and almost a mile and a half long, emerge from the woods at the base of Seminary Ridge.

Hundreds of battle flags bobbed along the front.

They moved forward in perfect formations guided by their officers—some walking and others on horseback, but all with upraised swords that glistened in the sunlight. Hundreds of battle flags bobbed along the front, giving the scene a festive air, as if this were a mammoth military review on some fantastic parade ground.

O’Kane watched, awestruck. He had never seen anything quite like it, but he knew that the purpose of the parade was not to display Confederate drilling prowess. What he could not know was that this desperate attempt to break the Union line was focused on the clump of trees at his back.

O’Kane walked to the stone wall, climbed up and faced his troops.

“Men, the enemy is coming,” he said, “but hold your fire until you see the whites of their eyes. I know that you are as brave as any troops that you will face, but today you are fighting on the soil of your own state, so I expect you to do your duty to the utmost.”

The irony of Irishmen defending a state, many of whose inhabitants detested their presence in it, and whose principal city had sent them off to war with a volley of bricks and stones, was not lost on those within earshot.

As if to underscore his last remark, O’Kane added: “If any man among you should flinch from that duty, I would ask the man next to him to kill him on the spot.”

O’Kane reached down with his right arm, unsheathed his sword and raised it above his head.

“And let your work this day be for victory or to the death,” he shouted.

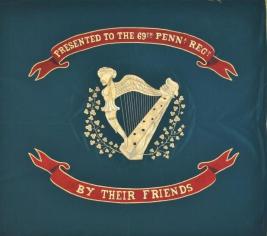

O’Kane put the sword back in its sheath, climbed down off the wall and ordered his color bearers to uncase the national standard and the regiment’s green flag with the gold harp on one side and the Pennsylvania coat of arms on the other.

He then moved among the companies of his regiment, speaking to the men and pointing occasionally in the direction of the Rebel infantry, which was moving in the direction of the Emmitsburg Road.

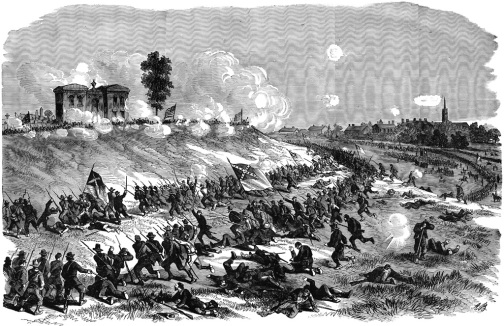

Major General George Pickett and Brigadier General James Johnston Pettigrew led 15,000 Confederate troops in an attack on Union lines along Cemetery Ridge on July 3, 1863, the final day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

By this time, the Union batteries had found the range of the Confederate columns and were blasting holes in the neat formations. But as each group of rebels went down in the wake of an exploding shell, other men moved in to fill the gap, and the advance continued.

General George Pickett’s division, on the right of the Rebel line, executed a half left wheel to face the clump of trees, in front of which O’Kane had again taken up his position. On Pickett’s left came the division of General James Pettigrew, moving with parade ground precision despite the shelling.

Meanwhile, two guns from Cushing’s battery had been wheeled down to the stone wall and loaded to fire canister shot. The lethal spray from these and other Union guns was taking a heavy toll on the Rebel infantry, which now was forced to climb over or crawl through fences on both sides of the Emmitsburg Road. Once past this obstacle, the survivors bunched together into one compact line—several ranks deep—and rushed towards the wall.

While some firing started on the left of the 69th’s line, most of the troops followed O’Kane’s order and waited until the Rebels were within shouting distance. Then, on command, a volley of flaming musketry erupted from behind the stone wall, halting the advance and taking down an appalling number of Rebel soldiers.

For a few seconds, those still standing were immobilized by the concussion. Then, instinctively, some came together and returned the fire while others continued the mad rush to a spot where the stone wall turned 90 degrees back to the ridge.

This section of the wall had been manned by two companies of the 71st Pennsylvania Volunteers, but as a disorderly mob of several hundred screaming Rebels bore down upon them, the defenders ran back to the main body of their regiment, leaving a protected position on the 69th’s right flank available to the enemy.

Seizing the opportunity, a Confederate general waving a slouch hat on the tip of his sword suddenly emerged from the Rebel mob and began to lead his men over the wall at this spot.

When O’Kane saw what was happening, he ordered the three companies on the regiment’s right to change front and face the Rebels who were coming through the gap in the line. Despite the noise and confusion, two companies completed the maneuver, but the captain of the third was killed before he could execute it.

With his hat on the point of his sword, Confederate General Lewis A. Armistead leads Rebel troops against the 69th Pennsylvania Volunteers during Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863.

O’Kane looked to his right. His lieutenant colonel, Martin Tschudy was down and men were running to his assistance. More Confederates streamed over the wall. The fighting at the angle now was at point-blank range, with many of the combatants using their muskets as clubs.

O’Kane noticed that the Rebel general had dropped his sword and hat and was bent over clutching his stomach. He staggered a few steps, reached out for support to the muzzle of one of Cushing’s abandoned guns and collapsed. Now leaderless, the Rebel soldiers appeared disoriented, but a few managed to make their way up the slope and into the clump of trees and started shooting at the regiment from behind.

Along the rest of the wall, Rebel troops were using it as a rampart or trying to climb over. To close openings in his line and to gain some firing space, O’Kane ordered his men to back up several paces closer to the trees.

Then it happened. O’Kane was on the ground in excruciating pain. A minie ball had passed through his abdomen and he was bleeding profusely. In the time that it took to get a stretcher, O’Kane drifted in and out of consciousness, but he could hear from behind the trees the volleys of the Union regiments that had moved into position on the slope above him.

As he was lifted on to the stretcher, O’Kane was dimly aware that the firing had begun to diminish.

“The line held,” he thought. “The line held.”

A regiment of Irish tradesmen and laborers from Philadelphia, led by a publican, had stopped the best that Lee could send.

O’Kane slipped into a coma and died during the early morning hours of July 4.

His funeral procession on July 9 wound its way from his home on Florida Street to St. James Church in West Philadelphia, led by a brass band. His pallbearers were 16 Union Army officers—among them, three from the 69th who had been wounded at Gettysburg.

A Solemn Requiem Mass was celebrated and a eulogy delivered by the pastor. Then his casket was taken to Cathedral Cemetery and, after full military honors, lowered into an unmarked grave.

Without a headstone, however, there was no place for the epitaph he would have wanted:

“Here lies Col. Dennis O’Kane of the 69th Pennsylvania Volunteers. His regiment took the brunt of Pickett’s Charge and stood its ground.”

(The author wishes to express his indebtedness to the following Civil War historians: Frank A. Boyle, D. Scott Hartwig and Michael H. Kane. Without their extensive research, this story could not have been written.)

Walter Fox is a freelance writer and the author of Writing the News: A Guide for Print Journalists. This article originally appeared in Philadelphia’s Irish Edition of June 1999. (Photo of Dennis O’Kane courtesy of the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia. © 1999 Walter J. Fox Jr. (for reprint permission contact: wjfoxjr@verizon.net)

Have you ever thought about writing an ebook or guest authoring on other blogs? I have a blog based on the same subjects you discuss and would really like to have you share some stories/information. I know my subscribers would appreciate your work. If you’re even remotely interested, feel free to send me an e mail.|

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on meta_keyword. Regards|

Superb, what a website it is! This web site presents valuable information to us, keep it up.|

O’Kane was my 3x Great Uncle, I am a descendant of his brother John. Thanks for this story!

I believe I am.also a relative of Colonel O’Kane. My paternal grandmother was an O’Kane. On a trip to Ireland some years ago my Uncle took me to Park. We stopped at a house and during a chat with the owner he told us he had found an old picture in an oval frame. On showing it to us my Uncle recognized it as an Uncle of his. A great Uncle to me. My father was also given a small hardback book about the 69th found among my grandmother’s possessions. I was told it was a limited edition produced for the regiment but cant verify that.